In this post, I’ll describe my experience spending a few days in Cairo and cruising down the Nile river in Egypt. I took two weeks off before starting a new job at JP Morgan Chase on May 30th 2023. In that time, I traveled to Scotland, Jordon and Egypt. I had an amazing time in all three countries, specially Egypt. I got to learn about one of the most important civilizations in human history, which has left an indelible mark, specially with its architectural legacy. I also met some great people, ate delicious food and had time to relax, read and reflect. I highly recommend Egypt as a vacation destination.

Finishing this post has taken a lot of time and effort, partly because Egyptian history is so rich and complex and connecting my experience in Egypt to its historical context in a compelling way took a lot of effort. Hopefully this info will be of use to anyone interested in learning about ancient Egypt and some of its monuments that survive today, and what to expect on a visit to Cairo and cruise on the Nile river. As usual, I’ll start with general information about Egypt, show a timeline of major events in Egyptian history (focusing on ancient Egyptian civilization), discuss my observations on distinctive aspects of Egyptian culture and then describe each day of my trip to Egypt.

Egypt: General Info

Located on the northeast part of Africa, with the Mediterranean sea to the North and Red sea to the east, and home to the Suez canal, one of the most important waterways in the world, Egypt has served as the crucial link connecting northeast Africa with the Middle East for many millennia. Today, at 469 Billion $ of nominal GDP, Egypt is the second largest economy in Africa (after Nigeria) and an important US ally. However, Egypt stands out in how it continues to be defined by its distant past, rather than what it is today or what it was even 500-1000 years ago.

Ask anyone what image comes to mind when they hear “France”, and you’re likely to hear Eiffel tower, something about Napoleon, or something related to French wine or food. However, ask the same question about Egypt, and most people will say–“The Pyramids” and more specifically, “The Great Pyramid of Giza”. In the minds of most people, Egypt continues to be identified with the ancient Egyptian civilization that ruled an astonishing 5500 years ago, when France and much of Europe was settled by post-neolithic cultures about whom little is known and who barely left an imprint. As the saying goes–“man fears time, but time fears the pyramids!”.

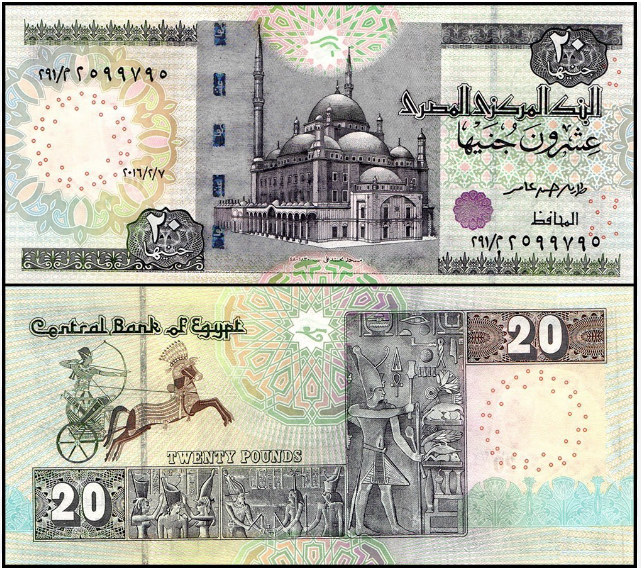

With 90% of its population identifying as Muslims and speaking Arabic as their primary language, modern Egypt is very different from the Egypt of the ancient Egyptians in its culture, language and religion. However the monuments built by the ancient Egyptians live on and continue to be a dominant force in modern Egypt. This is perhaps best illustrated by modern Egyptian currency notes, which bear an image of contemporary Egypt such as a mosque on one side and an image from ancient Egypt such as a relief carving showing ancient Egyptian gods on the other.

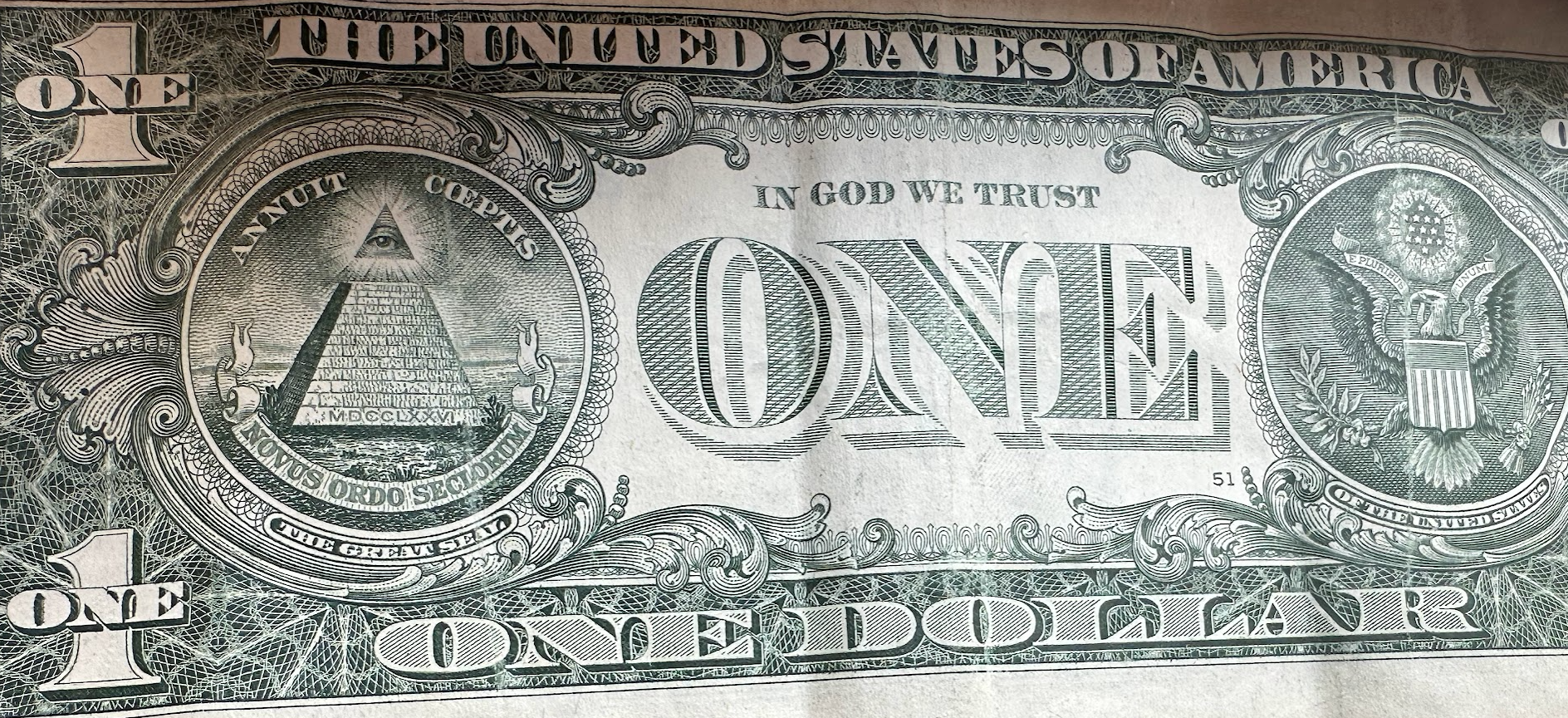

The achievements of the ancient Egyptians are truly a human heritage, and duly recognized and celebrated by cultures all over the world. In the United States, the 1 $ bill bears an image of the pyramids, the Washington monument is the tallest obelisk (a shape first used in the new kingdom of Egypt) in the world and the term “Pharaonic” has entered our lexicon to imply something impressively or overwhelmingly large and luxurious.

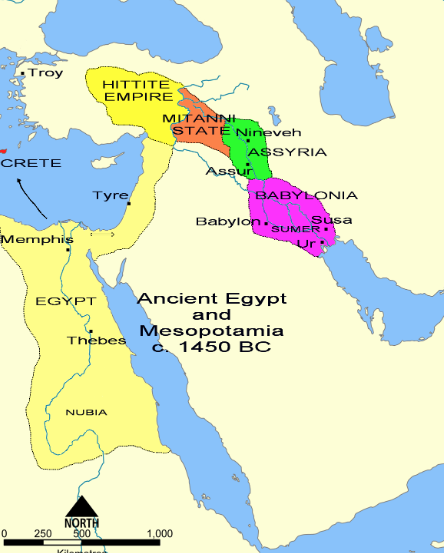

The Egyptian empire overlapped with several other bronze age civilizations such as the Hittites (1700 to 1200 BC in today’s Turkey and Syria), Assyria (2600 – 609 BC in today’s Syria), Mittani (1550 – 1260 BC in today’s Turkey and Syria) and Babylonians (1894–1595 BC and 620 – 539 BC). The ancient Egyptian empire was not the biggest, most powerful or the most populous empire of its time. What distinguishes the Egyptian empire from its contemporaries, is its longevity (3000 – 30 BC) and the vast scale of monumental architecture, much of which survives to this day.

Egypt’s contemporary empires also built massive buildings, but they were not as numerous and were sometimes made out of mud bricks which isn’t as durable as stone, and therefore destroyed by earthquakes or built over by succeeding civilizations. A good example is the Ishtar gate, the eighth gate to the inner city of Babylon constructed in 575 BCE by order of the Babylonian King Nebuchadnezzar II. Nothing remained of Ishtar gate or Babylon until it was excavated in the late 19th century and painstakingly restored. A smaller frontal part of the Ishtar gate was reconstructed after world war 1 and sits in the Pergamon Museum in Berlin. I had the opportunity to visit the gate during a visit to Berlin last year and was astounded by its majesty and beauty. However as you can see in the picture below, the gate looks rather out of place in a museum in Europe, far away from the city whose entrance it once graced.

The reason the Egyptians invested such time and effort in building their monuments was their belief in life after death and the megalomania of the Egyptian pharaohs who believed themselves to be god’s incarnate and wanted to build monuments that would last forever. Sam, the Egyptologist who led our excursions on the Nile river cruise told us that Egyptian belief in life after death stemmed from the cycle of the sun, omnipresent in Egypt that rose from the East and set in the West without fail every day. The Egyptians extended this idea to human life. The birth of a person was like the rising of the sun, life on earth like the sun traversing the sky from east to west and death like the disappearance of the sun over the horizon at the end of a day. Like the sun, a person would rise again, provided they are able to navigate the treacherous journey through the underworld. To help them along, Egyptian tombs were covered with magic spells intended to assist a dead person’s journey through the underworld, and into the afterlife.

From a practical standpoint, monuments built by the Egyptians survive, because they were built out of stone. However, these monuments were invariably tombs or temples associated with religious worship or celebrating the cult of the pharaoh, not palaces or residential buildings. The Egyptians themselves lived in dwellings made from mud brick, which beings porous is a better building material for the hot and dry conditions of the Egyptian desert. Almost none of these buildings survive, because mud brick isn’t a very durable material.

In a sense, the Egyptians succeeded in their goal to celebrate life after death. Ancient Egyptian civilization continues to live on in their monuments, long after the people who built them.

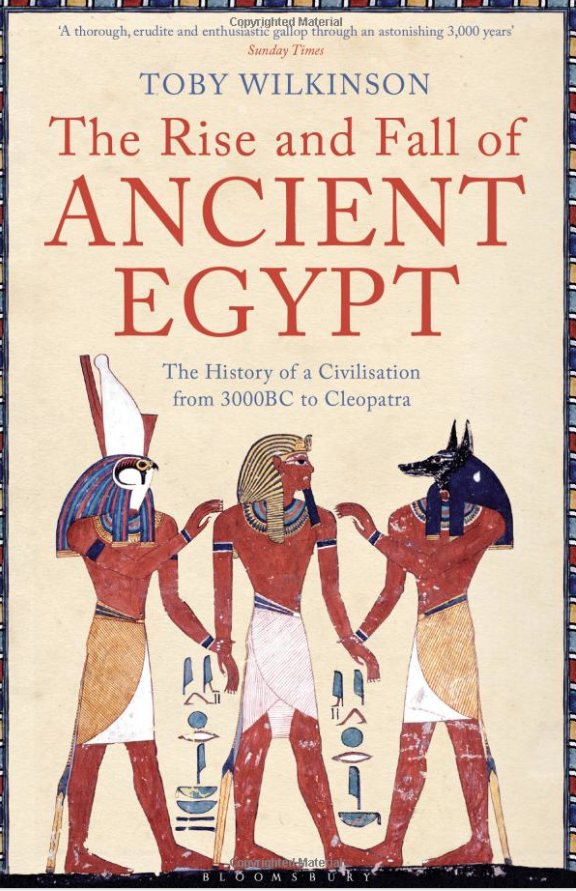

Before I left for this trip, I read an excellent book on Egyptian history called Rise and Fall of Ancient Egypt by Toby Wilkinson.

The book is well written, but quite detailed and can be bit of a slog, because the subject will be unfamiliar to most people. It certainly was to me, and I’m a huge history buff. However, the knowledge and context gained from the book proved invaluable during my trip. A general understanding of the broad sweep of Egyptian history and being able to place a monument in the proper context was instrumental in appreciating the significance of what I was looking at. As an example, we saw the the great hypostyle hall at the Karnak temple built by Seti I and Rameses II in ~1200 BC and later the Kon Ombo temple built during 180–47 BC by the Ptolemy dynasty, more than 1000 years later! At a first glance, the two look like very old and impressive buildings and it is easy to miss that their period of construction are separated by more than 10 centuries. When the coliseum in Rome was being built, Egyptian monuments were already considered antiquities! Sam, our guide told us the basic facts about the sites we visited, but there is so much to absorb during the visit (specially for the first time) that it is easy to miss out on the nuances and finer distinctions.

If you are short on time, I recommend reading part III (The Power and Glory) about the new kingdom and chapter 23 (The Long Goodbye) in Part V, about the Ptolemies.

Timeline of Egypt

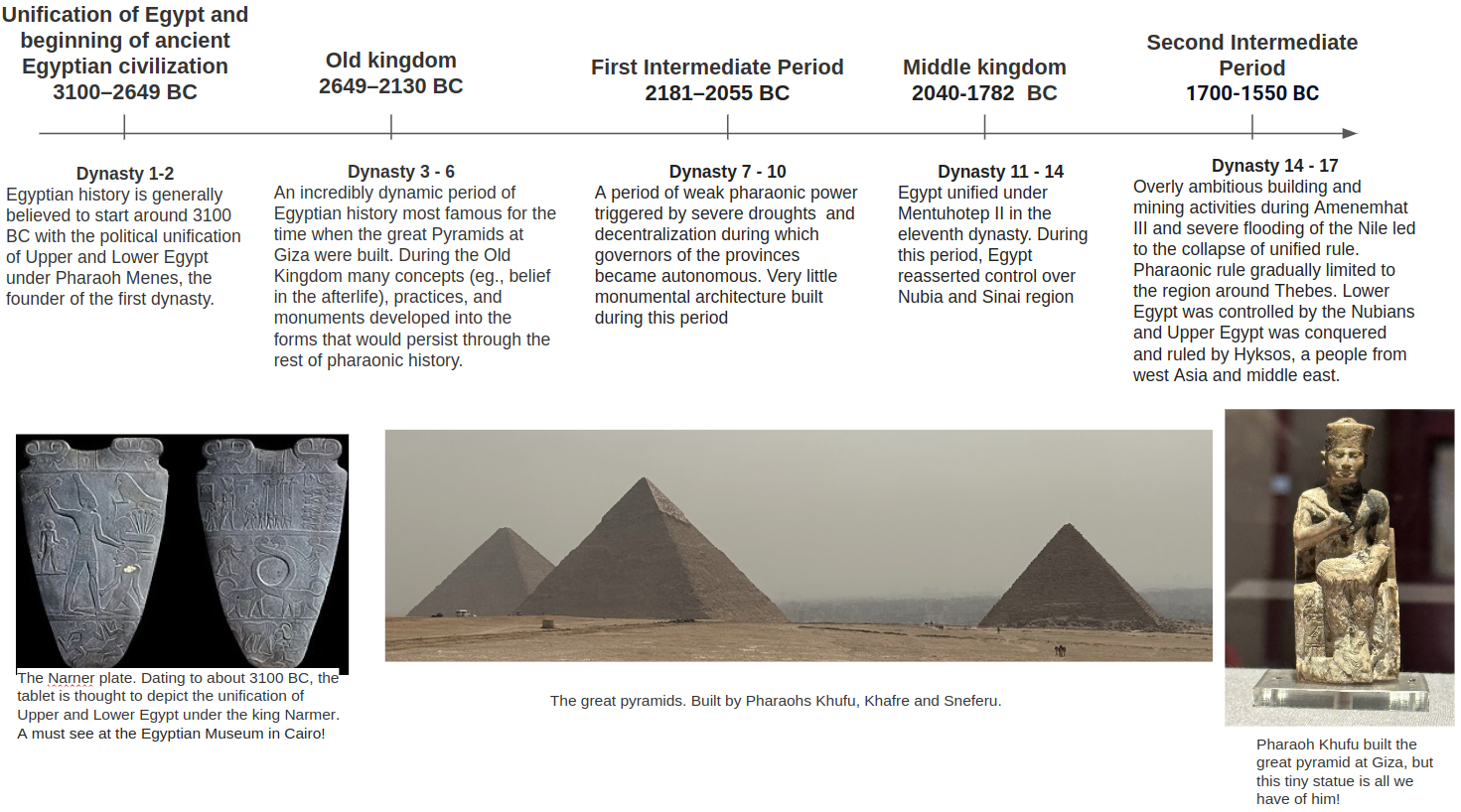

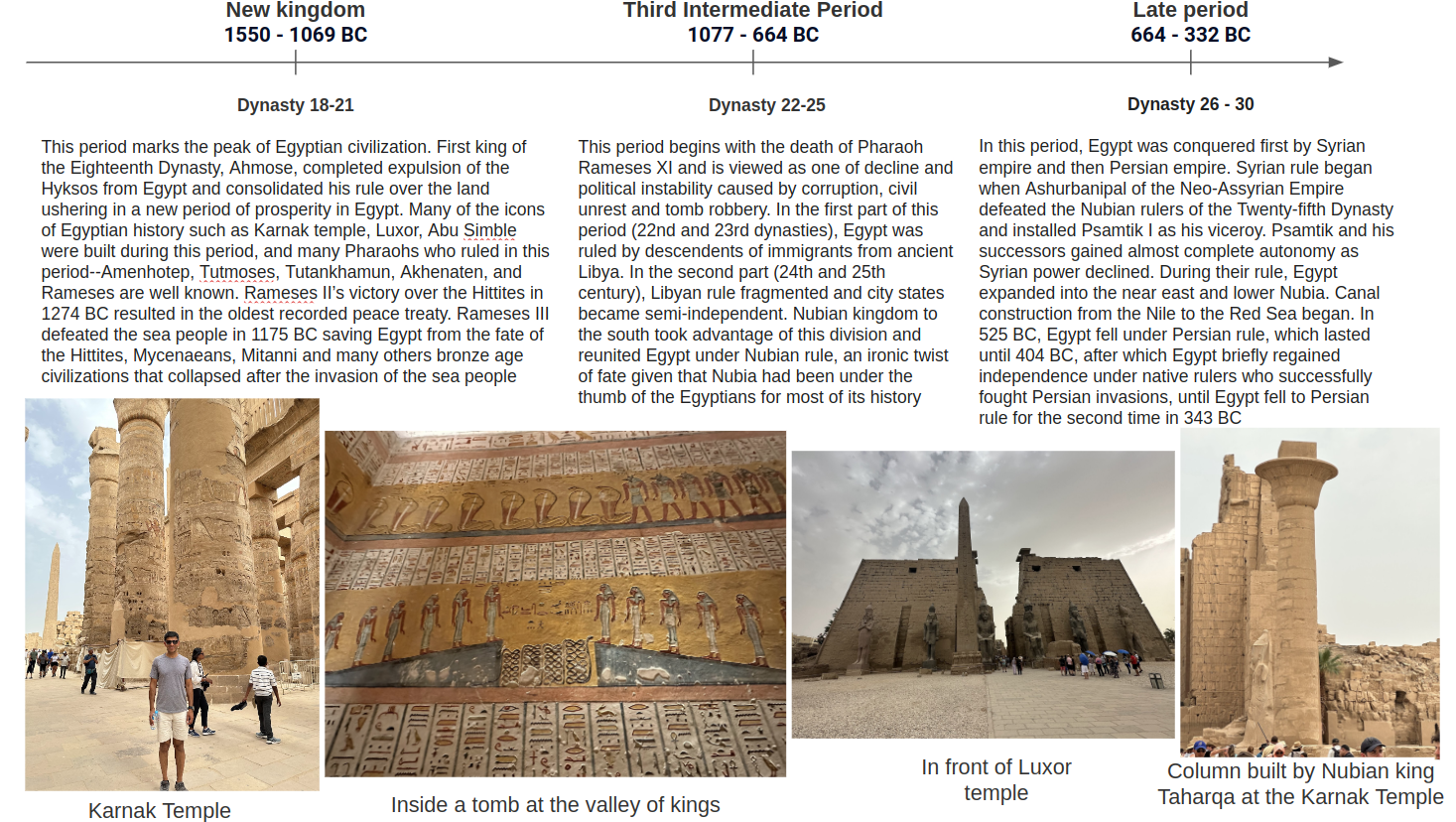

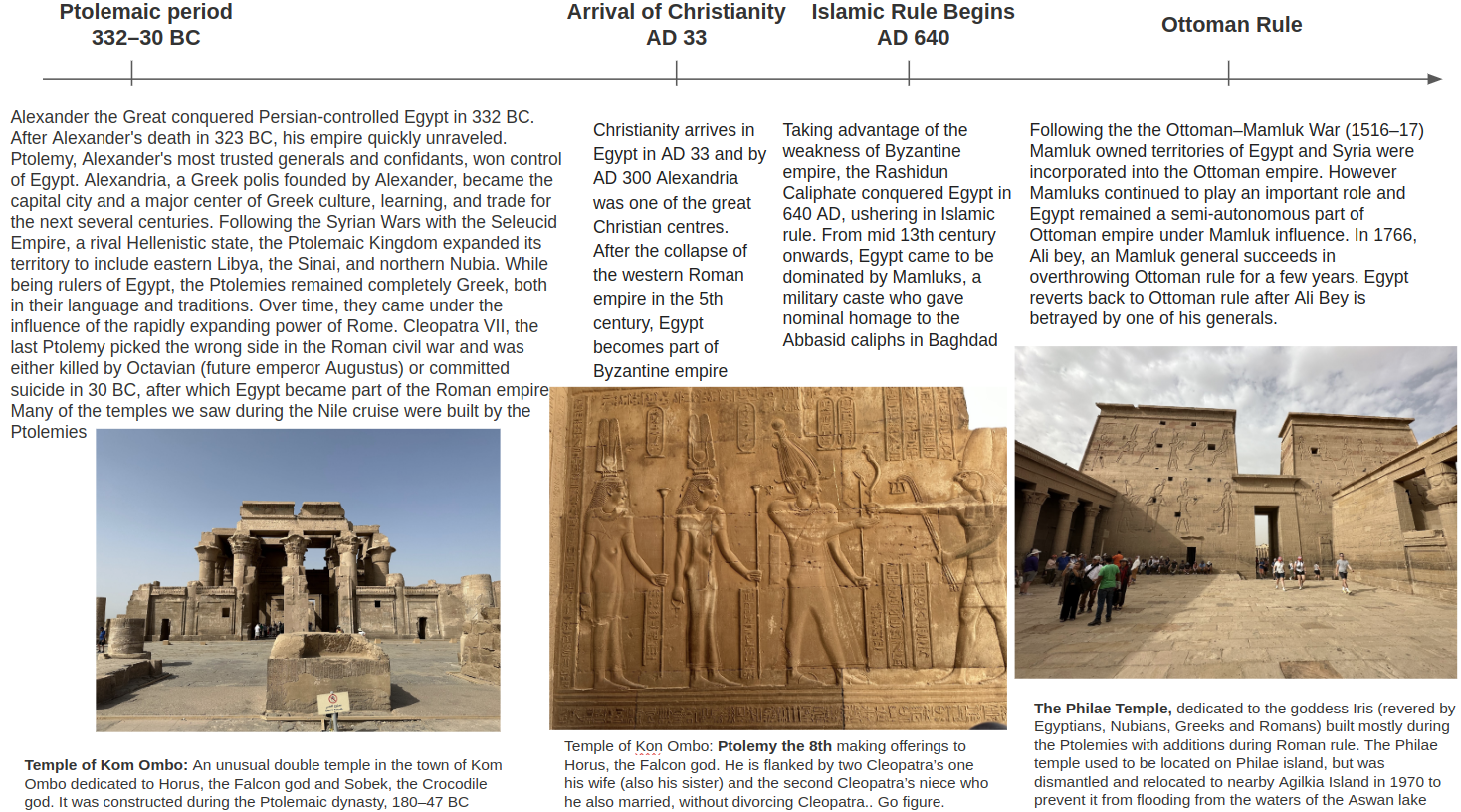

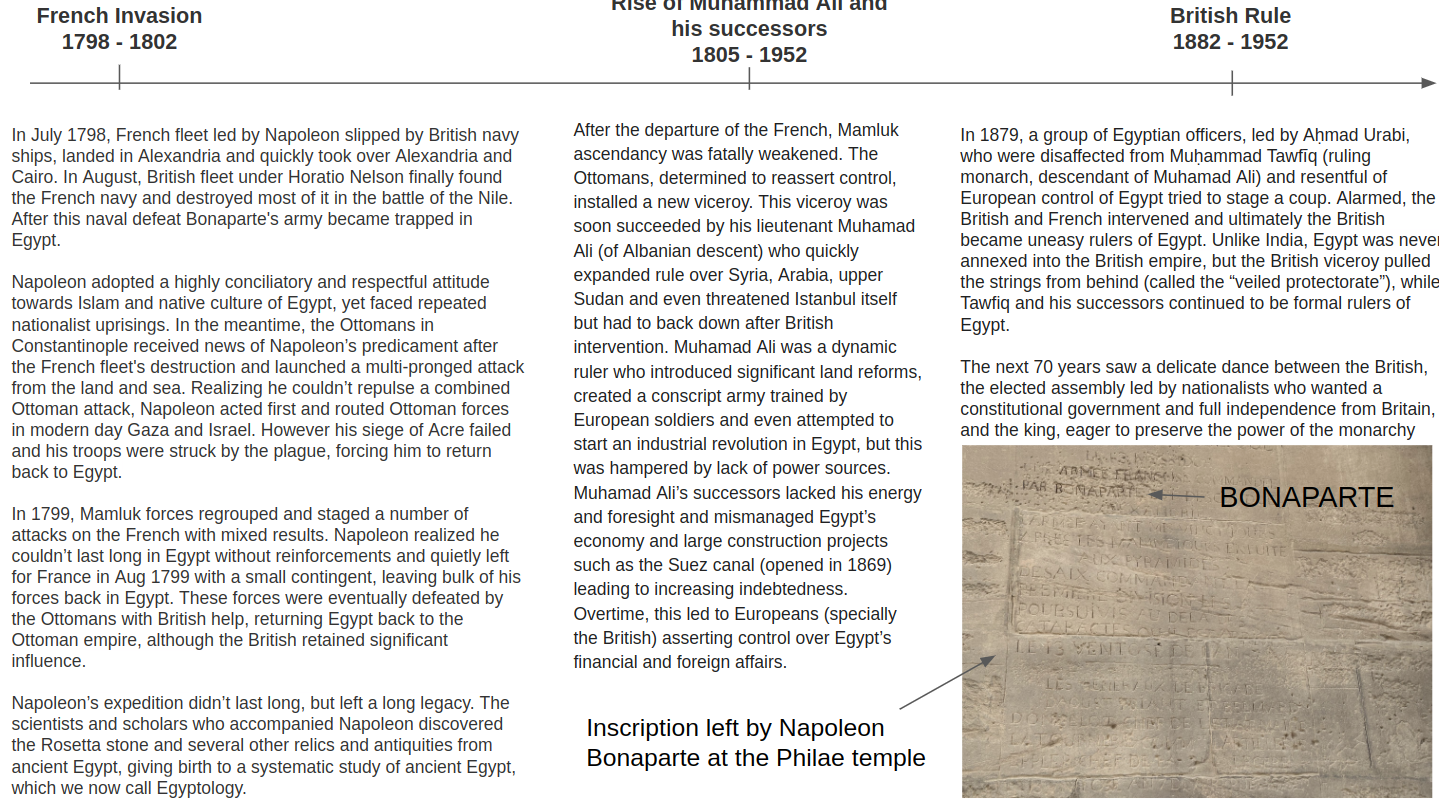

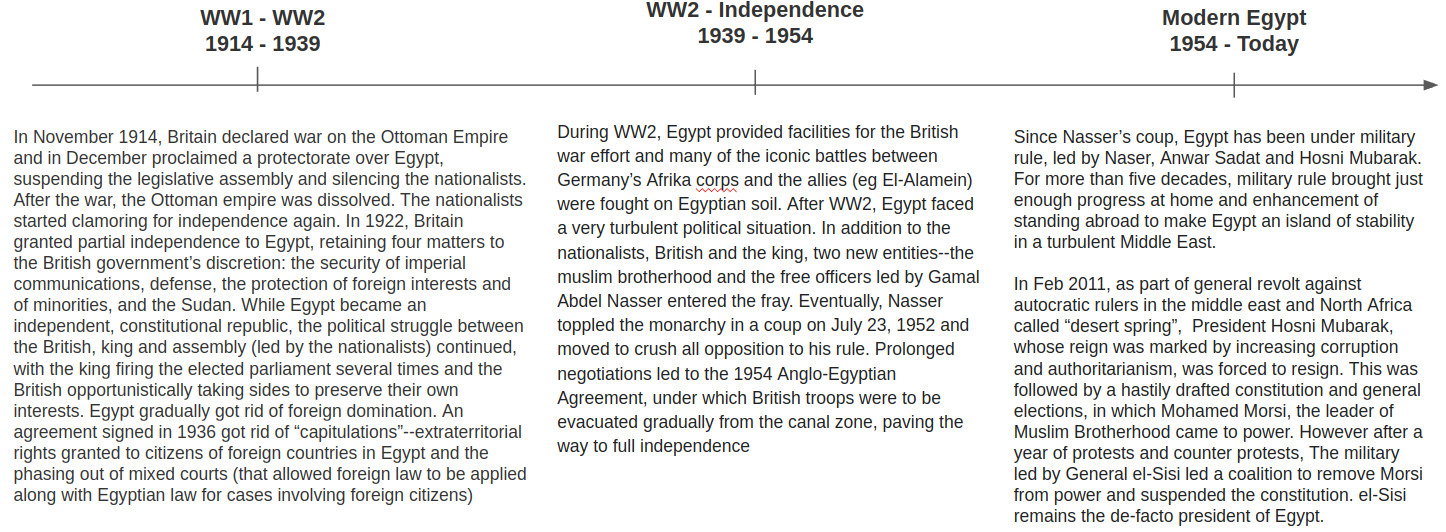

Below I show a timeline of the grand sweep of Egyptian history, focusing on developments in ancient Egypt, but also including what came after Egypt was incorporated into the Roman empire.

I’ll now proceed to describe a few concepts that you’ll encounter frequently in this blog and other literature about Egypt, some unique features of Egyptian history and culture and my own commentary.

Dynasties

You’ll encounter the term “dynasty” quite frequently in this blog and other literature on Egyptian history. A dynasty is loosely defined as a series of rulers sharing a common origin, or the turning of an era. The rulers are usually part of a common bloodline, but not always. For example, Horemheb is included in the XVIII dynasty, even though he was of common origin and not part of the bloodline of Thutmose III, the most illustrious of the XVIII dynasty rulers. Horemheb was succeeded by Rameses I, who ushered in a new era called the Ramesside period, and hence considered to mark the beginning of a new dynasty, the XIX dynasty. Some dynasties were extremely short-lived, such as the XXVIII dynasty consisting of just one pharaoh– Amyrtaeus who ruled for just 6 years. Thus, the concept of dynasty is loosely defined, and serves mostly to make Egyptian history easier to understand by partitioning it into logical blocks, akin to how European history is divided into Roman period, dark ages, medieval period, renaissance and so on.

Women Rule

Women were instrumental in shaping the course of Egyptian history, both in human and divine form. Let’s start with the divine. “Isis” is a household name today. Isis (Egyptian Aset or Eset) started divine life as a minor goddess in the middle kingdom gaining importance as the dynastic age progressed, until she became one of the most important deities of ancient Egypt. Her cult subsequently spread throughout the Roman Empire, and she is still worshiped today by some pagans. Isis was most often represented as a beautiful woman wearing a sheath dress and either the hieroglyphic sign of the throne or a solar disk and cow’s horns on her head. Isis was the wife (and sister) of Osiris and the mother of the falcon god Horus, one of the most prominent gods in the Egyptian pantheon. Osiris was murdered by his jealous brother Seth and later brought back to life by the magical powers of Isis who then gave birth to Horus. The story of this fratricide is depicted in carved reliefs all over the temples of Egypt.

Hathor, the cow goddess was the daughter of the sun god Ra and wife and consort of Horus. She was the goddess of many things: love, beauty, music, dancing, fertility, and pleasure. Every year, her statue would be carried in a boat to Edfu (temple dedicated to Horus) to be reunited with Horus. A festival celebrating their union would then begin.

Now on to the human. Women in ancient Egypt wielded power as regents to their underage sons and Pharaohs in their own right. The most famous is Hatshepsut. Hatshepsut (1507–1458 BC) was the daughter of Thutmose I and his wife Ahmose. Upon the death of her husband and half-brother Thutmose II, she ruled initially as regent to her stepson Thutmose III, who inherited the throne at the age of two. Several years into her regency, Hatshepsut assumed the position of pharaoh, making her a co-ruler alongside Thutmose III. In order to establish herself in the Egyptian patriarchy, she took on traditionally male roles and was depicted as a male pharaoh, with physically masculine traits and traditionally male garb. Hatshepsut’s reign was a period of great prosperity and general peace. One of the most prolific builders in Ancient Egypt, she oversaw large-scale construction projects at the Karnak Temple Complex, and built the temple of Hatshepsut near the valley of kings in Luxor (more on that later).

Besides Hatshepsut, other prominent female Pharaohs of Egypt were Sobekneferu and Twosret. Sobekneferu was the first historically attested female king of Egypt, ruling for 4 years. She ascended to the throne following the death of Amenemhat IV and was the last ruler of the Twelfth Dynasty of the Middle Kingdom.

Twosret (died in 1189 BC) was the last known ruler and the final pharaoh of the Nineteenth Dynasty of Egypt. She was thought to be the second royal wife of Seti II. After her husband’s death, she became first regent to Seti’s heir Siptah and became sole ruler after Siptah’s death.

Women are also depicted prominently in images and reliefs on Egyptian temples and likely played an important role in Egyptian politics and governance. For example, Rameses II built a temple for his beloved wife Nefertari next to his own in Abu Simbel.

Egypt was by no means a liberal society for women rights. Women were generally oppressed and even women pharaohs were considered illegitimate by later pharaohs. For example, the names of both Hatshepsut and Sobekneferu are omitted in the Abydos Table, a list of the names of 76 kings of ancient Egypt, found on a wall of the Temple of Seti I at Abydos, Egypt. I didn’t get to visit this temple, but it seems a good one to visit on the next trip to Egypt!

Thutmose III, the stepson of Hatshepsut, tried to remove his stepmother from the history books by tearing down her statues, defacing her monuments and removing her from all official records. Although, perhaps he can be forgiven for bearing a grudge against his step mother who started as his regent and ended up usurping the throne. Twosret met a similar fate. Her successor Setnakhte usurped the joint tomb of Seti II and Twosret but reburied Seti II in another tomb while deliberately replastering and redrawing all images of Twosret with those of himself.

Tomb Robbery

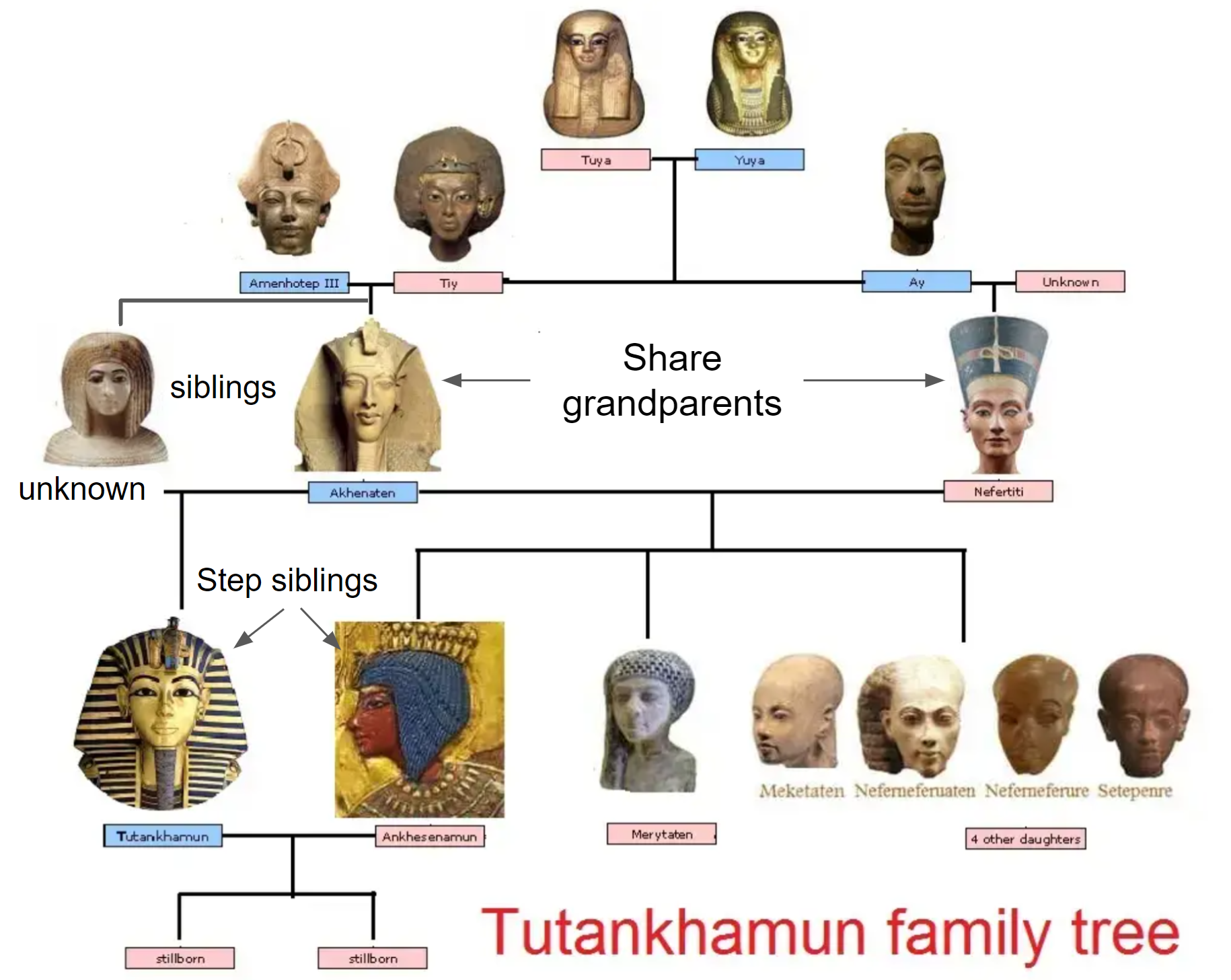

If you know of any pharaoh’s name, it is likely king Tut or Tutankhamun. He was actually a relatively insignificant pharaoh who ruled for a few years and died in his teens. The reason he is so famous is that by sheer luck his tomb escaped detection by tomb robbers and was found intact in the early 20th century with all the treasures he was buried with! King Tut’s tomb was the exception to the rule that most tombs inside the pyramids and valley of kings were robbed in antiquity. While thieves were after items that could not be traced or metals that could be melted down, they also ravaged the tombs, damaging human remains in the process. In the 20th dynasty, priests had become so concerned about the safety of the royal mummies that they removed the bodies of the pharaohs and hid them in secret caches – in a small shaft-tomb near Dayr al-Bahari and in the tomb of Amenhotep II, where they remained undetected until late in the 19th century. More on this later.

Hieroglyphic script

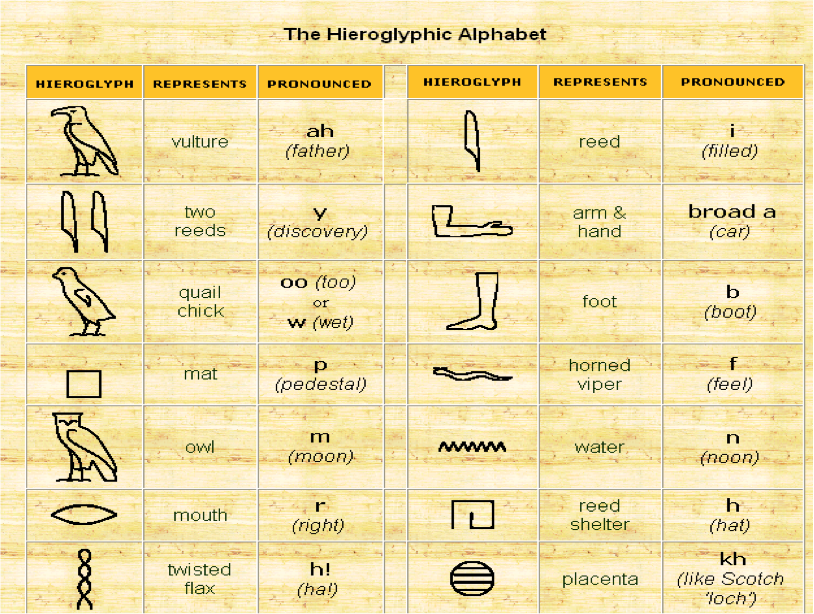

Beautiful picture-like symbols called hieroglyphs adorn Egyptian monuments. These were part of ancient Egyptian writing system, which was one of three scripts that evolved in the ancient near east during the fourth through first millennia BC. The others are the cuneiform script of Mesopotamia and the alphabetic script first used on a large scale in the Levant during the first millennium BC., and later became the basis for all alphabetic scripts used today. The word “Hieroglyphic” comes from “sacred” (Greek: hieros) and “sculpted” (Greek: glypho), likely because hieroglyphic system was used to write sacred inscriptions sculpted on temple walls.

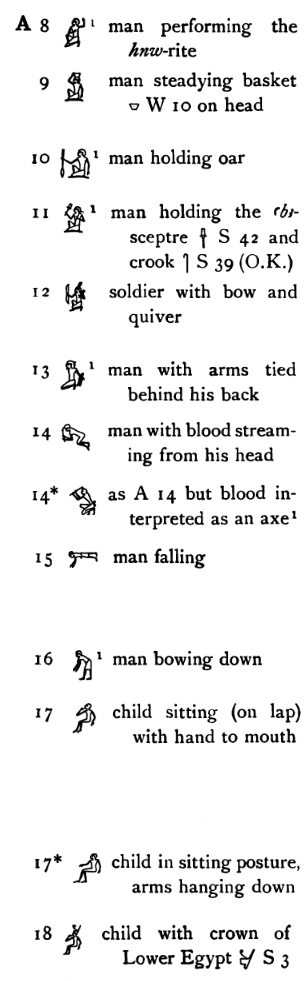

So how does the hieroglyphic system work? The section on ancient Egypt at the Met in NY has a great description of how hieroglyphic system works. Hieroglyphic writing uses images of things and beings. It does not, however, use a different image for each word in the language. Some hieroglyphs are picture signs, drawings of things they represented. Others are alphabetic, and represent sounds. There are thousands of hieroglyphs, but only about 500 were in common use. I show below the hieroglyphs that represent sounds (phonograms) and a few variations of the “man” pictogram (a sign that stands for what the picture actually depicts). This is an excellent resource if you want to see more examples.

The hieroglyphic writing system uses a combination of pictorial and phonetic writing system based on the rebus principle (which is the idea that symbols could represent sounds, rather than simply stand for the item they wished to represent). To give an example in English, imagine we use the picture of a door to write the two consonants ‘d’ and ‘r’ (Egyptian scribes ignored the vowels). We could then use the same sign to write the word ‘deer’ or any other words with d and r. Thus, we’d have to specify by additional means which word we mean in a particular instance. This specification was achieved by adding a vertical stroke to the sign of the door (d-r|) if ‘door’ was the word intended. If the d-r image is used to write “deer”, the picture of an animal would be attached. If we then wanted to use the d-r image to write the word ‘drive’ (d-r-v without the vowels), we needed to add the single letter ‘v’. To be perfectly clear, we may add an explanatory image that was not pronounced, such as the image of a car.

English reads from left to right, while Arabic reads from right to left. Which way was the Egyptian writing read? It could be written from left to right, right to left (most commonly seen) and vertically. One way of realizing the direction of the text is to see which way the hieroglyphs face. For example, the hieroglyph of a seated man ![]() . Depicted as he is, he faces to the left, thus the text following reads from the left to the right.

. Depicted as he is, he faces to the left, thus the text following reads from the left to the right.

After Egypt became part of the Roman empire, writing based on hieroglyphs started to fade from common use. Around the end of the 4th century AD, hieroglyphs had gone out of use, and the knowledge of how to read and write them disappeared. So how did we learn how to read hieroglyphs? The answer is the Rosetta stone, found by one of Napoleon’s soldiers while digging the foundations of an addition to a fort near the town of Rashid (Rosetta) in the Nile Delta in July 1799. The writing on the Stone is a decree, about Ptolemy V (204–181 BC). The decree says that the priests of a temple in Memphis (present-day village of Mit Rahina near Cairo) supported the king. The decree is inscribed three times, in hieroglyphs, Demotic (the cursive Egyptian script that developed in Lower Egypt during the later part of the Twenty-fifth Dynasty, used mostly for daily purposes, while hieroglyph-based writing was reserved for religious texts), and Ancient Greek. Because the inscriptions say the same thing in three different scripts, and scholars could still read Ancient Greek, the Rosetta Stone became a valuable key to deciphering the hieroglyphs!

After the French defeat in Egypt, the Rosetta stone was taken to Britain, where it remains today. It is one of the most popular exhibits at the British museum.

Incest

Today, the very thought of a sexual relationship with a brother or sister, or even a cousin inspires revulsion. However, in ancient Egypt, incest was practiced widely among the pharaohs and the high priests for strategic reasons, i.e., to preserve the symbolism which associates the pharaoh to a living god. As mentioned above, according to Egyptian legend, the god Osiris married his sister Isis who gave birth to the famed Horus, the Falcon god, one of the most significant deities through to Graeco-Roman times. Thus, by marrying a close family member, Egyptian kings were trying to preserve the cult of their divine origins. Incest was particularly prevalent during the 18th and 19th dynasties, and pharaohs such as Amenhotep I, Thutmose I, Thutmose II, Thutmose III, Amenhotep II, and Thutmose IV probably married half-sisters. According to DNA evidence, the famous Tutankhamun or King Tut, was the child born from a first-degree brother-sister relationship between Akhenaten and Akhenaten’s sister (name known). As a result, Tutankhamun suffered from congenital deformities which might have caused a walking disability. This was supported by the 130 sticks and staves found next to his mummy in his tomb. Perhaps partly as a result of genetic disorders, king Tut died in his teens, which ultimately resulted in the collapse of the 18th dynasty and a succession of military rulers under Horemhab and Rameses who didn’t have royal descent. King Tut married his half sister Ankhesenamun and had two stillborn children whose mummies were found in his tomb.

The Ptolemies, who came to rule Egypt after Alexander the great’s conquest of Egypt took incest to the next level. Arsinoe and her younger brother Ptolemy II engaged in a full brother-sister marriage, and the descendants of Ptolemy II had the tendency to follow his example. Of the thirteen Ptolemies who came to throne, seven engaged in full brother-sister marriages. The last Ptolemy, the famous Cleopatra VII, was the daughter of Ptolemy XII and his relative Cleopatra V, who was likely one of his sisters or cousins. It is indeed a wonder that the Ptolemies lasted for so many generations! The likely explanation of this practice among the Ptolemies (who were Macedonians by descent, and stuck to their Greek/Macedonian ways and didn’t even learn the native Egyptian language) was to legitimize Macedonian dynastic rule by adopting some Egyptian practices.

Closer to our time, incest was prevalent among the Habsburgs of Austria-Hungary with several marriages between close blood relatives such as first cousins, double-first cousins, and uncles/nieces. This resulted in high infant mortality and distinctive facial features such as the “Habsburg jaw”.

Hindu god Rama = Rameses?

I can’t help but notice the several parallels between Egyptian history and the Hindu religious pantheon. The names of pharaoh Rameses and Seti are quite similar to the Hindu god Ram and his wife Sita. The image of Rameses riding on his chariot and smiting his enemies at the battle of Kadesh brings to mind Ram’s 14 year exile where he journeys to Lanka to rescue his wife from the clutches of the evil demon king Ravana or the archer Arjuna riding his chariot against his enemies in the Mahabharata.

In ancient Egypt, every day in every temple, specially designated persons performed a ritual focused on making offerings of food, drink, clothing and ointment, to a divine being. The images of these rituals are the most common reliefs carved on Egyptian monuments. The practice of making offerings to the statue of a god continues to be a hallmark of Hindu religious practice. Growing up as a kid in India, I would accompany my parents to the temple every Tuesday. We’d buy some food from one of several hawkers outside the temple and present it before the statues of god and goddesses in the temple. We’d then distribute the food to poor kids and beggars outside the temple.

Egyptian gods such as the falcon god Horus, the crocodile god Sobek, the cow goddess Hathor etc., are often depicted bearing the head of an animal. Hindu deities are sometimes depicted in a similar way–most prominent example being lord Ganesh who bears the head of an elephant.

Statues of important gods such as Amun were usually kept deep in the interior of the temples of Karnak and Luxor, and only the high priests of the temple had access to these statues. Once every year, these statues were carried around town on a litter where they could be viewed by the general public. In modern Hindu temples, statues are generally kept in the interior of the temple and regularly attended to by priests who regulate access to the temple.

Finally, there are parallels between the Egyptian idea of judgement and life after death, and the notion of karma and reincarnation in Hinduism. Hindus believe that after the end of your life, your soul is presented before god and the balance of your good and bad deeds is evaluated. If you lived a godly life, you’ll be admitted into the kingdom of god, otherwise you’ll reenter the cycle of life and death, perhaps as a lower life form.

The historical timeline adds up. According to Wikipedia, the Upanishads which are the foundation of Hindu philosophical thought and its diverse traditions were composed around 800 BC. The epic Ramayana that tells the story of Rama was written between 8th to 4th century BC. Egyptian civilization peaked between 1500 – 1100 BC, after which Egypt was dominated by Syria and Persia that lie between Egypt and India. It is conceivable that Syrians and Persians introduced Egyptian ideas into India, and influenced the development of Vedic culture and Hinduism!

My Itinerary

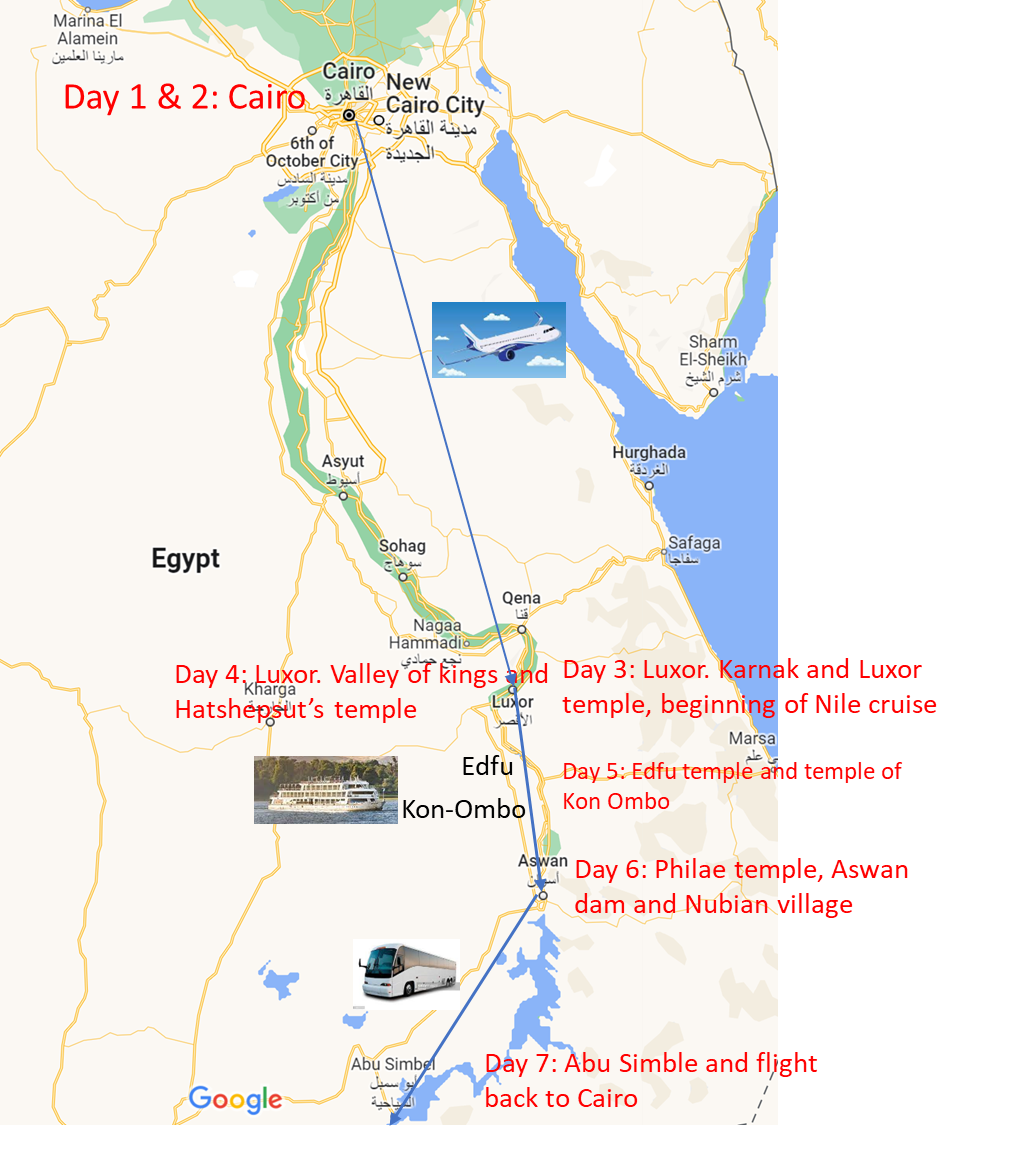

As shown in the picture below, I flew into Cairo from Jordon, spent a day and half touring the Pyramids and museums in Cairo. On day 3, we took an early morning flight to Luxor (known as Thebes in Egyptian times), the starting point of our Nile cruise and home to Karnak and Luxor temple and the valley of Kings and Queens. On day 4, we commenced our cruise upstream along the Nile, stopping at Edfu temple and temple of Kon Ombo on day 5. We arrived at our destination Aswan on the evening of day 5. On day 6, we visited Philae temple and Nubian village. On day 7, we drove 3 hours each way to visit Abu Simbel and took the evening flight back to Cairo.

I’ll now describe the main activities for every day of my itinerary along with its historical context. Happy reading!

Leave a Reply